Though this is far from my first study abroad semester, Prague is the first place I’ve studied in a non-English-speaking country. Before coming here, however, I really wasn’t too nervous about the language gap. Prague is a very international city, with almost all young people speaking English as a second language, and so I felt like there wasn’t a real necessity for me to learn to speak any Czech. In fact, I debated whether or not I should even take the elective Czech class at all. After all, how useful could it be? Czech is not a very widely spoken language, and I couldn’t see how I could even use Czech skills outside of Czechia itself. However, driven by my passion for languages, I ultimately decided to embrace the opportunity. I have not regretted it since, and fully recommend that you do the same if you find yourself in a similar situation when you study abroad.

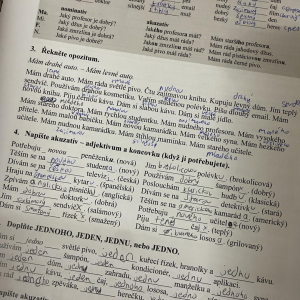

Czech has a particularly steep learning curve, but the process of learning it is an incredibly rewarding endeavor. Among its more “unique”

features are seven distinct cases for words, new grammatical concepts such as “aspect”, and almost alien sounds like ř or ů. While languages like Spanish and French are categorized by the US State Department as "Category 1" languages—considered relatively easy to learn alongside Dutch and Portuguese—Czech falls into the more daunting "Category 3," on par with Greek, Farsi, and Albanian, and harder than other languages such as German, Swahili, or Malay. I found that the first few classes were a struggle as I tried to wrap my head around the basics, but it got easier and easier over time. Many programs in countries like Czechia are fully aware that you’re coming in with limited to no knowledge of the national language, and they’re not going to overwhelm you with its more complex aspects. Instead, you’ll be learning the easiest and most important aspects of the language (I still can only reliably use two of the seven grammatical cases!). However, though I am only realistically scraping the surface of the language, I have still experienced its benefits in various ways.

The benefits of speaking any degree of Czech are both tangible and intangible. Tangibly, speaking a survival amount of the native language of the country you’re living in is always a good idea. Though English is almost ubiquitous in Prague, I have taken trips to more regional and far less international cities like Pardubice and Beroun, and my meager Czech helped out a great deal there. I was able to ask for directions, order food from a menu, and read signs at museums. Even within Prague, there are times when I am able to read signs with no English translation, and it makes my life far easier. Thus, even if most Praguers can speak English, there are tangible benefits to being able to converse a little with them in their native language. To add on to that, I found that during my trips to Poland and Slovenia, my knowledge of Czech has allowed me to understand some basic phrases in many other Slavic languages. I have found that my newfound Czech skills are in fact more transferable when outside Czechia than I previously thought, as I can occasionally recognize words in Polish, Ukrainian, or Russian.

However, the intangible benefits of taking Czech far outweigh their tangible counterparts. For one, many of the cities people study abroad in are inundated with tourism. Prague is no exception, especially during peak season when tourists actually outnumber residents in the older districts. The overwhelming majority of these tourists, there for a few days, have made no effort to learn Czech or Czech traditions. This leads many Praguers to believe that their city is being overcommercialized - in other words, the real essence of the city has been diluted and Anglicized to profit off of an extremely lucrative tourism industry. Therefore, even though my Czech is clearly not native, I have noticed that Praguers genuinely appreciate that you have gone through the effort of trying to respect their language and culture. Even greeting someone with a simple “dobrý den” instead of “hello” or thanking someone with a “děkuji vám” instead of “thanks” goes a long way, and being able to go further, such as ordering at a restaurant fully in Czech, clearly leaves a strong, positive impression. It is a small way of showing that you have done your research, and can communicate with them in the way that they feel most comfortable. You display that you value the city not just for its tourist value, but for its intrinsic culture, and that you want to engage with it at its most genuine level.

Before this semester, I genuinely thought that taking a Czech class would not be a valuable use of my time. After all, I could have used that class time to fulfill a GW requirement, or could have taken less classes and given myself more time to travel either domestically or abroad. But as I have spent time in Czechia, I have grown to understand that even if Czech isn’t required, it opens so many doors to this country that I couldn’t open had I not made the effort. Whether it be the ease of navigation, breaking the ice quicker with native speakers, or showing that you’ve made the effort to respect the culture, I have found that learning the native language of my study abroad destination is worth it. It’s a small gesture of gratitude towards the city that provided me with this once in a lifetime study abroad experience.

Joshua Blaustein

Spring 2024

Semester in Prague - Charles University (East & Central European Studies)

Elliott School of International Affairs

International Affairs Major

The Global Bachelor's Program